Data tokens on this page

Financial Solutions

Financial Solutions

The Risks of DIY Investing

The implication that investor under-performance has for long-term wealth accumulation is staggering.

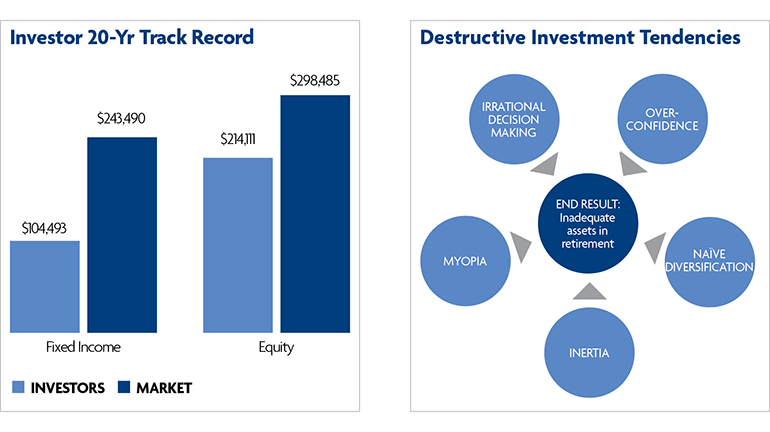

Despite unprecedented and ever-increasing access to economic and investment data, study after study has shown that the track record of private investors is not encouraging. Moreover, they typically do not realize they underperform the market. In fact, over the 20 year period ending in 2018, the average equity fund investor achieved a 3.88% annualized return whereas the average S&P 500 Index returned 5.62%. Fixed income investors fared even worse, realizing an average return of 0.22% compared to 4.55% by Barclays Aggregate Bond Index.1

As the chart to the right shows, a $100,000 equity investment made 20 years ago and managed by an average equity investor would have been worth nearly $85,000 less at the end of last year than an S&P 500 index-tracking fund. That same investment, managed by an average fixed income investor, would have been worth little less than half of what an investment in a Barclays Aggregate Bond Index-tracking fund would have been after 20 years.

The overriding reasons behind investor's underperformance are behavioral biases that cause them to act on emotion and deep-seated misperceptions about investment risk.

Behavioral biases relate to how we process information to reach decisions and the preferences we have.2 They can affect all types of decision-making, but have particular implications in relation to money and investing.

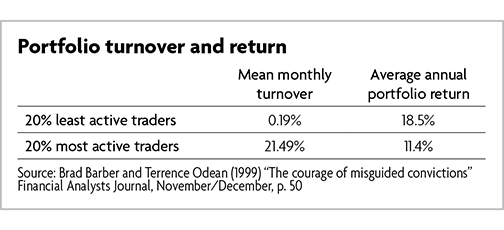

These biases tend to sit deep within our psyche and may serve us well in certain circumstances. However, in investing they often lead us to move into market tops and bail out at market lows. These biases, combined with common misunderstandings about investment risk can be thought of in five categories of destructive investment tendencies that private investors face as shown in the graphic to the right.

At Wintrust Wealth Management, we see evidence of these tendencies in our clients’ thinking all the time. A desire to remove asset classes perceived to be risky or unfamiliar (real estate, international equities, etc.) from their portfolios which, in fact, actually increases volatility. A preference for a particular asset class or investment vehicle based on the most recent year’s performance. A request to wait on putting cash to work until the (presumed) impending market correction comes. They are deep-seated in many and adversely affect the ability to realize long-term financial goals.

To reduce the influence of these destructive tendencies, investors first need to understand what they are and how they influence their thinking.

Overconfidence

Psychological studies have shown that all of us tend to have unwarranted confidence in our decision making. This trait appears universal, affecting most aspects of our lives. Researchers have asked people to rate their own abilities, for example in driving, relative to others and found that most people rate themselves in the top third of the population. Few people rate their own abilities as below average, although by definition, 50% of all drivers are below average. Many studies—of company CEOs, doctors, lawyers, students, and doctors’ patients—have also found these individuals tend to overrate the accuracy of their views of the future.3

Overconfidence is linked to the issue of control, with overconfident investors believing they exercise more control over their investments than they do. In one study, affluent investors reported that their own stock-picking skills were critical to portfolio performance. In reality, they were unduly optimistic about the performance of the shares they chose, and underestimated the effect of the overall market on their portfolio’s performance.4 In this simple way, investors overestimate their own abilities and overlook broader factors influencing their investments.

Overconfidence has direct implications for investing, which can be complex and involve forecasts of the future. One way in which this is evident is in investors overestimating their ability to identify winning investments. Traditional financial theory suggests holding diversified portfolios so that risk is not concentrated in any particular area. Misguided conviction can weigh against this advice, with investors or their advisers ‘sure’ of the good prospects of a given investment, causing them to believe that diversification is therefore unnecessary.

Overconfidence also tends to produce stubborn investing. This can be seen in ‘conservatism bias’, which describes the idea of the decision maker clinging to an initial judgement despite new, contradictory information.

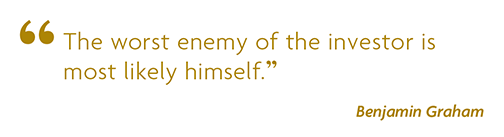

A third means by which overconfidence adversely effects investing decisions is in the tendency to trade too frequently, often with a negative effect on returns. A study of U.S. investors with retail brokerage accounts found that more active traders earned the lowest returns.5 The table to the right shows the results for the most and least active traders. For the average investor switching from one stock to another, the stock bought underperformed the stock sold by approximately 3.0% over the following year. Whatever insight the traders think they have, they appear to be overestimating its value in investment decisions.

Underlying this overconfidence are a number of attitudes investors tend to hold of which they should be mindful. Foremost is a characteristic known as ‘self-attribution bias.’ In essence, this means that individuals faced with a positive outcome following a decision will view that outcome as a reflection of their ability and skill. However, when faced with a negative outcome, this is attributed to bad luck or misfortune. This bias gets in the way of the feedback process as decision-makers block out negative feedback and miss the opportunity to improve future decisions.

Similarly, hindsight bias fuels overconfidence. The statement “I knew the whole time this would happen” shows that we have an explanation for everything after the fact. This hindsight bias keeps us from learning from our mistakes. Even if prices rise, we keep buying. “What the heck, I’ll buy it again because it’s cheaper than last time,” we say. In other words, the typical private investor buys high and sells low—wasting a lot of money in the long term.

Additionally, ‘confirmation bias,’ which is the phenomenon of supporting our own opinions with selective information, fuels overconfidence. Investors seek confirmation for their assumptions. They avoid critical opinions and reports, reading only those articles that put their decision in a positive light. This is also common in the media. Business journalists will report on innovative, creative companies that are all making a profit in bull markets. However, they rarely point out that not all companies using those same criteria succeed, as it would undermine the reporting narrative. We cannot avoid reading the headlines about price gains and booming markets or the multitude of success stories and, unfortunately, these stories attract the interest of many amateur investors.

Inertia

Inertia is the failure to take action. A related issue is a tendency for emotions to sway investors from a course of action to which they have committed (i.e. having second thoughts). The desire to avoid regret is one driver of these behaviors. Inertia can act as a barrier to effective financial planning, stopping investors from saving and making necessary changes to their portfolios. A fundamental uncertainty or confusion about how to proceed lies at the heart of inertia. For example, if an investor is considering making a change to their portfolio, but lacks certainty about the merits of taking action, the investor may decide to choose the most convenient path—wait and see. In this pattern of behavior, so common in many aspects of our daily lives, the tendency to procrastinate dominates financial decisions.

Another driver of inertia is the so-called ‘disposition effect’ associated with our natural aversion to loss. Behavioral finance suggests investors are more sensitive to loss than to risk and return. Some estimates suggest people weigh losses more than twice as heavily as potential gains. For example, most people require an even (50/50) chance of a gain of $5,000 in a gamble to offset an even chance of a loss of $2,000 before they find it attractive.6 The idea of loss aversion also includes the finding that people try to avoid locking in a loss.7 Consider an investment bought for $10,000, which rises quickly to $15,000. Investors are often tempted to sell in order to lock-in the profit. In contrast, if the investment dropped to $5,000, investors tend to hold it to avoid locking in the loss. The idea of a loss is so painful that investors tend to delay recognizing it. More generally, investors with losing positions show a strong desire to get back to break even. This means investors show highly risk-averse behavior when facing a profit (selling and locking in the sure gain) and more risk tolerant or risk seeking behavior when facing a loss (continuing to hold the investment and hoping its price rises again).8

Research done to test this idea using data from a U.S. retail brokerage found that investors were roughly 50% more likely to sell a winning position than a losing position, despite the fact that tax regulations make it beneficial to defer locking in gains for as long as possible, while crystallizing tax losses as early as possible. It also found that the tendency to sell winners and hold losers significantly harmed investment returns.

Naive Diversification

Behavioral finance research suggests investors sometimes struggle to apply the concept of portfolio diversification in practice. Evidence suggests that investors use ‘naïve’ rules of thumb for portfolio construction in the absence of better information.9 One such rule has been dubbed the ‘1/n’ approach, where investors allocate equally to the range of available asset classes or funds (‘n’ stands for the number of options available). This approach ignores the specific risk-return characteristics of the investments and the relationships between them.

Another common example of naïve diversification is the tendency for some investors to hold extreme portfolio allocations. On the one hand are aggressive investors who only hold all-equity portfolios. On the other hand are ultra-conservative investors who are reluctant to hold anything other than bonds. Many such investors need the help of an investment professional to ensure a balance of risk and return in portfolios.

Naive diversification also occurs when investors apply their well-documented preference to invest in familiar assets, which they often mistakenly associate familiarity with low risk. This ‘home bias’ manifests itself in high portfolio weights in assets from an investor’s own country. They are more familiar with and confident about local investment opportunities, so despite the fact that it is much easier than in the past to diversify investments across geographies, investors tend to go with what they know and can easily understand. In so doing, they miss out on important diversification opportunities that can not only lower risk but improve returns. For more on home bias and how to avoid it, see our paper, An International Investing Primer, from April 2015.

Home bias also is apparent in the tendency of investors to buy shares in the companies for which they work. In doing so, investors may become over-allocated to their company’s stock and the unsystematic risks that come from being under-diversified. Individuals that are over-allocated to company stock take the risk of having their assets and their income significantly reduced should the company go through a period of financial difficulty.

Myopia

Myopia, or short-sightedness, distorts the decision-making of many investors. Of the many forms of myopia, the tendency to chase trends is arguably the strongest bias. Researchers studying behavioral finance at the University of California found that 39% of all new money committed to mutual funds went into the 10% of funds with the best performance the prior year.10 Although financial products often include the disclaimer that “past performance is not indicative of future results,” many investors still believe they can predict the future by studying the past. The study found that investors who weighted their decisions on past performance were often the poorest performing when compared to others.

Myopic loss aversion is another related phenomenon which was coined by Shlomo Benartzi and Richard Thaler in their seminal behavioral finance research paper in 1995. Their research showed that investors would allocate more to stocks, and thus assume more risk, if they made their decisions at longer intervals. Investors that check on the values of their portfolio with great frequency are more likely to be subject to this particular bias. Given that most investors now have the ability to check on their portfolio’s valuation in real time, with great ease, they subject themselves to the pain of losses with great frequency. This pain, caused by myopic loss aversion, can easily cause them to stray from a well-thought-out investment plan. This is especially true in bear markets when the frequency and intensity of the pain are high. Thus, investors become susceptible to buying high and selling low.

Irrational Decision Making

Researchers have documented a number of biases that affect the way in which we filter and use information when making decisions.11 In some cases, we use basic mental shortcuts to simplify decision-making in complex situations. Sometimes these shortcuts are helpful, though in many cases they can mislead.

One form of this irrationality is anchoring, or the process of becoming fixated on past information and using that information to make inappropriate investment decisions. When investors are influenced by this bias, they may become fixated on a particular sell-price target, even if new information is available or the investing landscape has shifted significantly. They become stuck and may ride markets to the bottom if they cannot let go of what they think the price “should” be. Furthermore, if the price drops below the psychological anchor, investors often become more likely to buy because the stock seems cheap, as if it were on sale at the supermarket. This is driven by a desire to make up for their initial losses. “I can’t believe it! The price is 50% lower! That has to be a record low.”

Another form of irrational decision-making lies in the notion of ‘representativeness bias’ which reflects decision-making based on a situation’s superficial characteristics rather than a detailed evaluation of the reality. A common financial example is for investors to assume that shares in a high-profile, well-managed company will automatically be a good investment. This idea sounds reasonable, but ignores the possibility that the share price already reflects the quality of the company and thus future return prospects may be moderate. Another example would be assuming that the past performance of an investment is an indication of its future performance.

Investors also suffer from representativeness bias when they evaluate fund managers. Investors are often drawn to a manager with a short track record of beating market averages over a few years. Meanwhile, they show less interest in a manager with a much longer track record that has exceeded averages by only a small margin. Statistically, the manager with the long-term track record has the stronger case to make about skill. But investors tend to look at the manager with the short-term track record, and believe that the record of superior performance will continue.

The way information is presented influences investors’ decisions and can also lead to irrationality. For instance, there is a significant difference in whether a sum is presented as a loss or a missed profit, even if these terms mean the same thing. This so-called ‘framing effect’ applies to everything in life. Imagine having dinner at a friend’s house and being told that she made the sauce with 80% fat-free cream. Do you think she would have bought the cream if the package labeled it 20% fat?

The framing effect also extends into how investors tend to think about their portfolios. Finance theory recommends that all investments be treated as a single pool, or portfolio, and that the risks of each investment be considered in the context of others within the portfolio. Rather than focusing simply on individual securities, traditional financial theory suggests investors consider their wealth comprehensively, including their house, company pensions, government benefits, and ability to produce income. However, investors—by and large—tend to focus overwhelmingly on the behavior of individual investments or securities. As a result, in reviewing portfolios investors tend to fret over the poor performance of a specific asset class or security or mutual fund. These ‘narrow’ frames tend to increase investor sensitivity to loss. By contrast, by evaluating investments and performance at the aggregate level, with a ‘wide’ frame, investors tend to exhibit a greater tendency to accept short-term losses and their effects.

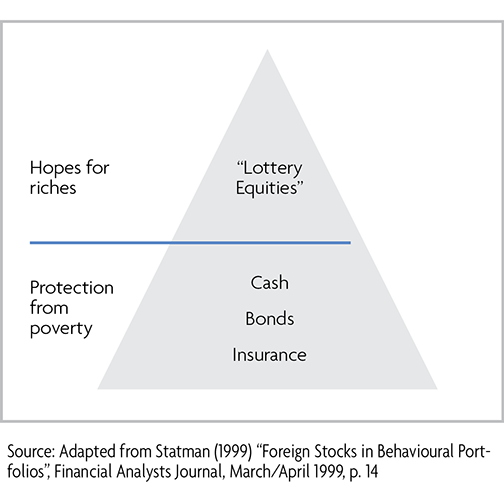

A final form of irrational investment decisions that many private investors exhibit is ‘mental accounting,’ or the process of making distinctions that are not reflected in financial reality. In so doing, investors pay less attention to the relationship between the investments held in the different mental accounts than traditional theory suggests is prudent. This natural tendency to create mental buckets also causes investors to focus on the individual buckets rather than thinking broadly, in terms of their entire wealth position. A second form of mental accounting is the distinction made between money in the bank and money made on the financial market. The latter, known as ‘house money’, is often placed at a greater risk than bank balances, which usually come from savings. Conversely, losses incurred are often viewed separately from paper losses. In essence, mental accounting makes investors think that a dollar is not worth a dollar—a dangerous attitude. This idea explains why an investor can simultaneously display risk-averse and risk-tolerant behavior, depending on the mental account about which they are thinking. It is why individuals can buy at the same time both ‘insurance’ such as Treasuries and ‘lottery tickets’ such as a handful of speculative stocks. The base layers represent assets designed to provide ‘protection from poverty’, which results in conservative investments designed to avoid loss. Higher layers represent ‘hopes for riches’ and are invested in risky assets in the hope of high returns. The theory also suggests that investors treat each layer in isolation and do not consider the relationship between the layers. Established finance theory holds that the relationship between the different assets in the overall portfolio is one of the key factors in achieving diversification.

Investor Biases in Action

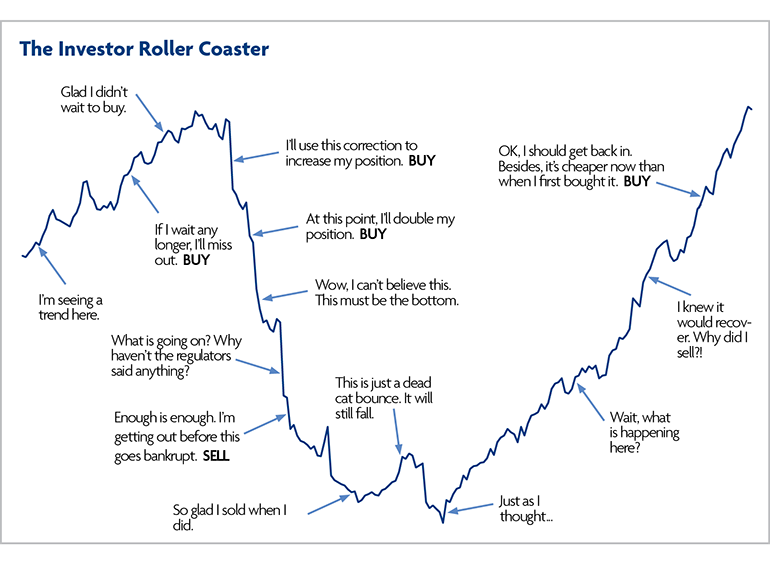

To appreciate these biases, consider a hypothetical investor and the investment roller coaster in the below diagram. The markets are on the rise, and stock exchanges are registering record highs. Our investor follows developments in the bull market with baited breath. Business journalists report on innovative, creative companies that are all making a profit in these markets, putting out headlines about price gains and booming markets. Unfortunately, the media rarely mention the companies that fail using those same criteria (confirmation bias). After a certain amount of watching from the wings, our investor decides to participate in the uptrend before it is too late (chasing trends). With the wind of so many success stories beneath his sails, our investor erroneously believes he has little chance of failing (overconfidence).

Our investor begins to look for familiar company names or those he has heard in the media or through friends when trying to find a good investment (availability bias). He eventually finds a promising pharmaceutical company, and begins to support his opinions about it with other publicly accessible information, making the mistake of looking for only positive information (confirmation bias, again). Report after report indicates that the company has done very well over the past two years (representative bias). Suppose that while researching the profits of the pharmaceutical company, our investor finds an interesting analyst report in a reputable business journal that projects the company to have a 20% chance of generating a 10% excess return over the S&P 500 in the coming year. He probably would not have been so intrigued if he had read that there was an 80% chance of the company generating a less than 10% excess return over the S&P 500 (framing effect).

Although it is speculative, our investor decides to invest in the company thinking, “I have some capital gains realized earlier this year. I can take some risk with a long-shot” (mental accounting).

Our investor monitors his position and it does well initially. He thinks, “Thank goodness I didn’t wait any longer.” Later he begins to see concerning reports emerge about the prospects of an important product in the company’s pipeline, though he is reluctant to give as much credence to those as he did the reports used to make his initial investment decision (conservatism bias). As the stock begins to sell-off, our investor’s response is to buy more stock: “I’m taking advantage of the correction and reinforcing my position,” or, “Great, I’ll double my position at this price” (anchoring bias). As the stock continues to fall, the investor does not sell off his investments (disposition effect). In addition, he wants to earn back the acquisition cost from his investment. The stock continues to plunge and our investor becomes increasingly anxious.

All of these considerations—expenses already incurred (the purchase price), not wanting to regret the decision, or engaging in mental accounting—lead to irrational decisions and can cost a lot of money. Checking his stock’s performance daily—or even multiple times a day—our investor becomes ever more keen to the pain of loss and short-sighted in his thinking. Eventually, he reaches the point where he can no longer take it: “Enough is enough! I’m never buying equities again!” Our investor liquidates his position, thankful to have retained at least a portion of his investment. Then the prices drop a bit more and our investor feels his decision was validated. “Good thing I sold it all,” he thinks.

Eventually the stock becomes oversold and begins to recover. Initially he is very cautious and does not trust the rebound. Despite small price gains, the investor is convinced that “it’s still going to drop.” The share price does in fact drop again and the investor feels vindicated. “It’s just as I said…” he tells himself (hindsight bias). He becomes more confident again. Then the stock begins a sharp increase. Our investor is as surprised by this development as he was by the sell-off. “Now what’s going on?” he wonders. The investor needs a little time to get back on board with the fast-paced market. Eventually the stock rallies to a point where our investor feels a restored sense of optimism. He decides to invest again in the stock thinking, “What the heck, I’ll buy it again because it’s cheaper than last time” (anchoring, again).

Our investor’s story is an all-too common one and illustrates the biases and misperceptions that drive the typical private investor to buy high and sell low—wasting a lot of money in the long term.

Guarding Against Destructive Tendencies

Do you see a bit of yourself in any of this? If you do, perhaps the best advice for individual investors is this: Avoid trying to outsmart the markets and instead work to outsmart yourself, and bear in mind the value that an investment professional brings to the table.

Working with an Investment Professional

You likely did not build your own house. You likely do not make your own clothes, practice medicine on yourself, or serve as your own attorney. You almost certainly did not build your own car. The time, skill, and expertise required to do so is prohibitive for most. Similarly, in the complex world of investment management, doing it yourself often ends up being costly, time consuming, and ineffective. A professional Financial Advisor brings expertise to the table (to combat naïve diversification), objectivity (to protect against myopia, inertia, and irrational decision-making), and experience (to guard against overconfidence). However, for a relationship with a professional to function best, investors need to recognize their own biases when they rear their heads. To that end, here are some investing axioms to bear in mind (see inset) and suggestions for topics to discuss with your Advisor.

Understand that the best way to avoid the pitfalls of human emotion is to have trading rules. Those might include selling if a stock drops a certain percentage, not buying a stock after it rises a certain percentage, and not selling a position until a certain amount of time has elapsed. Dollar-cost averaging is another good way to reduce regret—and make your head clearer for smart investing.

In terms of rebalancing, using a regular schedule for guiding decisions can help investors avoid being swayed by current market conditions, recent performance of a ‘hot’ investment or other fads. To weed out home bias, discuss different investing strategies than you typically use with your advisor and then consider employing those that are appropriate for meeting your unique financial goals. Finally, realize that if you find a trend, it is likely that the market identified and exploited it long before you. Last year’s winners are often this year’s losers.

1. DALBAR Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior 2018 Advisor Edition

2. Shefrin, Hersh, 2000. Beyond Greed and Fear: Finance and the Psychology of Investing. Chapters 1-3.

3. Barber and Odean (1999), ‘The courage of misguided convictions’ Financial Analysts Journal, November/December, p47.

4. Werner De Bondt (1998), ‘A Portrait of the Individual Investor,’ European Economic Review.

5. Brad Barber and Terrence Odean (1999) ‘The courage of misguided convictions’ Financial Analysts Journal, November/December, pp 41-55.

6. Montier, James (2002) Behavioral Finance Wiley p21-22.

7. Barber and Odean (1999) p42.

8. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (1979) ‘Prospect Theory: An analysis of decision making under risk’ Econometrica 47:2, pp. 263-291.

9. Bernartzi, Shlomo and Richard H. Thaler. ‘Naive Diversification in Defined Contribution Savings Plans.’ American Economic Review 91(1), (2001): 79-98.

10. Investopedia.com

11. Shefrin (2000) Chapters 1-3.

Start the Conversation

Where will your financial journey take you? A Financial Advisor helps you navigate the terrain, avoid pitfalls, and keep you on track to achieve your financial goals.